The shoulder complex: it is way more complicated than you think!

In our experience, we believe the general public is poorly educated on the human shoulder. Humor us and play along with the following game. In your opinion, are the following true or false:

1. The shoulder joint is simply a ball-and-socket joint.

2. The shoulder joint is mostly stabilized by boney connections.

3. The ROTATOR CUFF (or as many say, the rotar or rotary cuff) is one muscle.

4. The neck, back, and shoulder are not related to one another.

5. Posture doesn’t affect how the shoulder moves.

6. You do not need to strengthen the shoulder if you have an elbow or wrist injury.

I am sure you can see where we are going here. All of the above questions are in fact FALSE. Throughout this blog, we will address the above questions and educate you on the shoulder complex.

The shoulder joint is actually comprised of 4 joints.

As insinuated in the title, the shoulder complex is much more complicated than most think. In fact, it is actually made up of 4 different joints that must collectively operate in order to successfully move. In order for you arm to reach overhead efficiently, all 4 joints must coordinate.

1. Sternoclavicular (SC) joint:

Anatomy – The SC joint is the connection between your sternum and your collar bone (or clavicle). It is the only form of bone connection between the shoulder and body. This is a saddle joint, meaning that one bone is shaped like a “saddle” and the other like a “rider”. Also, it has a small disc that sits between the bony structures. This small joint is exceptionally important. Since it is small, its bony connection is not very strong, therefore it must rely on the surrounding ligaments for stability. Muscles, such as the sternocleidomastoid (SCM), pectoralis major and subclavius attach to this region.

Biomechanics – Although it does not seem like the SC contributes much to mobility, it moves a lot and is an important player in overhead motion and shoulder horizontal abduction/adduction (bring hands away and in front of face). In order to complete an overhead motion, the clavicle must elevate slightly and rotate inferiorly. When bringing your hands in front of your face/chest, the clavicle must move posteriorly on the sternum. In fact, it has been found that the SC joint can rotate up to 50 degrees and is responsible for at least 4 degrees of motion for every 10 degrees the shoulder moves overhead.

Possible Injury – Joint restrictions at the SC joint are common in patients with shoulder impingement. Our physical therapists at Block Chiropractic and Sports Physical Therapy are highly training in analyzing joint movement and finding restrictions at the SC joint. Often times, patients’ SC joints can become hypomobile, or stuck. When this happens, it can cause pinching in the shoulder during movement. Additionally, the SC joint can get stuck in an elevated position. It is possible that this is responsible for the pinching pain patients get in their shoulder when they are trying to lower from the overhead position. The muscles that attach to the SC joint (SCM, subclavius and pectoralis major) can become spasms and alter movement as well. Another possible injury can occur in the small disc that resides between the clavicle and the sternum. The disc often degenerates over time. In fact, in your 70’s and 80’s, it is likely that this disc is minimally inflated. This degeneration can lead to clicking and grinding, as well as pain in the area. Finally, it is rare but possible that the SC joint can dislocate under trauma.

2. Acromioclavicular (AC) joint:

Anatomy – The AC joint is where the other end of the collar bone attaches to a structure called the acromion. The acromion is the bony prominence that overhangs above the humerus. The acromion typically has one of three shapes: 1) flat (more space), 2) curved (a little less space) and 3) hooked (least space). The AC joint is diarthrodial, meaning it can move freely in great amounts. Additionally, it is covered by a joint capsule that allows both dynamic (muscles) and static (ligaments) stability. There is a small disc in the AC joint that often degenerates beginning in your twenties, with significant changes happening by the time you are in your forties. Finally, the deltoid, SCM, trapezius and pectoralis major all attach and act on the AC joint.

Underneath the acromion lies the subacromial bursa. A bursa is a fluid sac that provides “cushion” to the underlying structures. It decreases friction and protects muscles and tendons from getting caught in small joint spaces. Also underlying the acromion, are the tendons of supraspinatus (rotator cuff muscle) and long head of biceps.

Biomechanics – The AC joint moves every time the shoulder blade moves, since the acromion is technically part of the shoulder blade. The AC joint is responsible for 5-8 degrees of clavicle rotation during overhead movement. It plays a crucial role in maintaining the coordination between the shoulder blade and clavicle during shoulder movement. Here at Block Chiropractic and Sports Physical Therapy, our physical therapists have learned how to access the AC joint during examination. They have learned that the AC joint has a posterior/inferior (back and down) motion that when lacking, can contributing to decreased shoulder abduction and external rotation.

Possible Injury – As stated above, the AC joint is a common location for degeneration in the shoulder. Degeneration can lead to poor mobility and pain with elevation. Additionally, it is important to note that a hooked acromion can cause such little space in the shoulder that impingement can result. This leads to pain and pinching sensations during shoulder abduction, flexion or even external rotation. Finally, the AC joint is a frequent location of dislocations during falls. When you land either directly on the shoulder or on an outstretched arm, you put the AC joint at risk for dislocation.

3. Scapulothoracic (ST) joint:

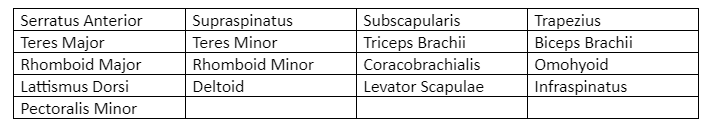

Anatomy – The ST joint refers to the shoulder blade (scapula) moving on the thoracic spine and connected rib cage. It actually spans the second through seventh ribs. The scapula is made up of several important bony parts where muscles and other bones are attached. Most importantly, the previously mentioned acromion and glenoid labrum are parts of the scapula. Seventeen muscles attach and act on the shoulder blade (see below). These muscles are important for not only the 6 movements that can occur at the scapula, but also because there is no bone-to-bone connection besides the AC joint. Therefore, the muscles provide stability and mobility.

Biomechanics – As stated above, there are 8 movements that can happen at the shoulder blade. It can elevate, depress, protract (move forward along rib cage), retract (pinch shoulder blades together), tilt anteriorly or posteriorly, and rotate upward or downward. In order for someone to reach overhead, the ST must move in a 2:1 relationship with the glenohumeral (GH) joint (mentioned below). The ST movement accounts for nearly 1/3 the full movement overhead. During shoulder flexion (reaching forward), the shoulder blade goes through depression, upward rotation and posterior tilt. The shoulder blade has to move frequently so the glenoid can maintain congruence with the humerus. The ST joint contributes slightly less to abduction, but does contribute 30-60 degrees. For the purpose of this blog, we will only address flexion and abduction, but understand that the ST plays a HUGE roll in shoulder movement.

Possible Injury – In our opinion at Block Chiropractic and Sports Physical Therapy, we believe that more often than not, the ST joint is responsible for shoulder pain and injury. When there are muscle imbalances between the trapezius, serratus anterior, levator scapulae and rhomboids for example, the shoulder blade is unable to move correctly during overhead movement. This causes the head of the humerus to move poorly in the glenoid which can lead to impingement, labral degeneration, and much more.

Have you ever looked at someone’s shoulder blades and noticed that you can see them a lot? For example, you may notice they sit far away from the spine and tend to stick out from the body. This is called winging of the scapula, and is not a good sign. This means that muscles, more specifically the serratus anterior, are under-recruited and working inefficiently. This typically indicates instability and poor movement during shoulder motions. Often times, overhead athletes under-develop this posterior chain and increases their incidence of injury.

4. Glenohumeral (GH) joint:

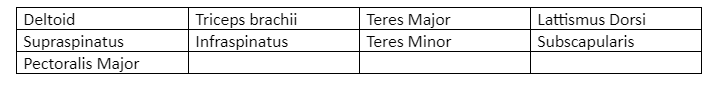

Anatomy – The GH joint is the typically ball-and-socket joint that everyone thinks of when they think “shoulder”. It is the articulation between the head of the humerus and the labrum created by the shoulder blade. The labrum sits in in a cavity known as the glenoid fossa. This cavity functions to extend the socket and make it deeper to allow for greater congruence between the bones. The GH has the greatest degree of movement out of the four joints mentioned. There are multiple ligaments surrounding the GH joint that provide it with stability and several muscles that attach and act on the humerus (see chart below). The rotator cuff is responsible for the majority of action at the GH joint. The muscles that comprise the rotator cuff are the 1) supraspinatus, 2) infraspinatus, 3) teres minor and 4) subscapularis.

Biomechanics – The shoulder can move in several different directions: 1) flexion, 2) extension, 3) abduction (away from body like snow angel), 4) adduction (toward body), 5) internal rotation, 6) external rotation, 7) horizontal adduction (clapping hands out in front of chest at shoulder level) and 8) horizontal abduction (moving hands away from chest at shoulder level). Additionally, a combination movement can occur called scaption – which is an overhead movement between the planes of flexion and abduction (about 45 degrees). The biomechanics of the GH joint are just as complicated as the ST joint and again for purpose of the blog post, we will cover only the basics.

The supraspinatus is the muscle most recruited when conducting overhead movement. Additionally, the deltoids play a role as well. In order to rotate the shoulder (i.e. open a jar, reach behind back to put bra on), the other rotator cuff muscles are called upon. Internal rotation is performed by the supraspinatus and subscapularis (as well as the pectoralis major, teres major and lattisimus dorsi). External rotation is performed by the infraspinatus and teres minor.

The humeral head moves on the glenoid to accomplish overhead movement. The humeral head must relocate posteriorly in order to accomplish flexion and internal rotation, and anteriorly to achieve extension and external rotation. Additionally, the head of the humerus moves downward in the joint to perform abduction and flexion.

Possible injuries – A traumatic event can of course lead to GH dislocation or fractures. However, more commonly, multidirectional instability occurs at the joint. Since the humeral head doesn’t sit deep in the labrum and it is held together by only ligaments and muscles, the shoulder is susceptible to instability. This causes greater movement that are warranted with “clicking/cracking/popping.” This can cause pain and dysfunctional movement which can lead to a cascade of other injuries.

As stated in a previous blog about overhead athletes, rotator cuff and biceps tendonitis’ or tears can occur and affect the GH joint as well.

In Conclusion:

Hopefully, after reading this blog you are able to correctly answer the beginning questions. Here at Block Chiropractic and Sports Physical Therapy, we understand how complicated the shoulder complex is. However, we have immense skills and knowledge to conduct a thorough examination of all of the aforementioned joints and musculature. We have a plethora of exercises to address various combinations of muscle imbalances, instabilities, strains, and post-surgical injuries. DO NOT ignore shoulder pain because it can progress and worsen if it is not quickly addressed. Visit our Smithtown or Selden offices and see how a shoulder screen may benefit you or someone you know.